The Independent Music Publishers International Forum (IMPF) has published its second Global Market View report. It spells out the impact of the pandemic globally, spotlights important growth in previously overlooked markets, makes very strident calls for a change in how revenues – notably those from streaming – are carved up and argues that publishers and songwriters need to see their shares of the spoils grow significantly.

The full report is available for free here. Below we pick out the most interesting points and (to some ears) the most controversial proposals in the report to consider where the independent publishing world could – and, indeed, should – be moving in the coming years.

The impact of the pandemic was keenly felt by indie publishers

This will come as no surprise to anyone that publishers’ revenues were badly affected by the global pandemic, but the IMPF has put a figure on the decline experienced in 2020. It suggests that global music collections slipped by 10% and came as a direct result of the pandemic – notably due to the near absence of live music and decreased ad revenues from broadcasters.

It adds that the total value of global music copyrights in 2020 was €28.6 billion and, of that, record labels took 64.9% while publishers took the remaining 35.1%. It notes that the label share of the total pie grew in 2020 compared to 2019 when record companies took 61% in 2019. The IMPF says this “asymmetry keeps growing” as labels take more of the overall spoils and publishers see their cut shrink.

Indie publishers took just over a quarter of the overall publishing market

Of the estimated €6 billion (i.e. 35.1% of €28.6 billion) in 2020, just over a quarter (28%) went to indie publishers – giving them a total of €1.68 billion for the year. This means indie publishers accounted for 5.87% of the total value of global music copyrights in 2020.

Digital cushioned the blow and online licensing has had to work harder to make up the shortfall…

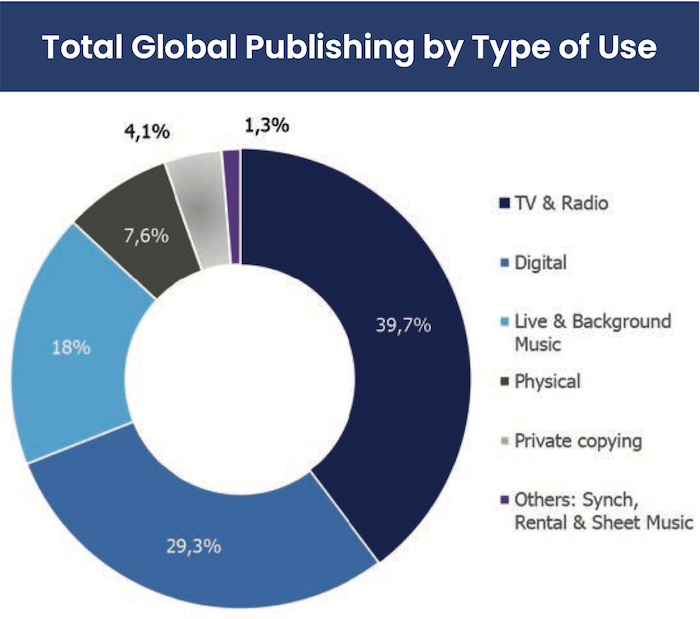

While the market slipped by 10%, the IMPF asserts that the decline “would have been much greater” had it not been for growing digital income “that boosted international revenue flows”. Digital actually became the second-biggest source of income for publishers that year, overtaking live music and background music income.

Despite a decline of 4.4% from 2019, radio and TV continued to dominate as the largest source of music publishing royalty payments in 2020 (holding 39.77% of the total, equal to €3.25 billion). Digital leapfrogged into second place with a 29.3% share (equal to €2.39 billion), although that was less about a phenomenal boom online and more about live and background revenues nosediving by 45%.

With other revenue sources shut down or severely compromised, online licensing had to work harder and go wider in 2020 than ever before. IMPF notes that “many CMOs quickly reallocated their resources into online licensing” as it became clear that the live business was going to be on hiatus for some time. This increased emphasis on the digital side of the business drove growth in the sector of 16.2%.

Source: IMPF

… but there is a growing disparity between what publishers get from digital and what record labels get – and this has to be recalibrated

Right from the foreword, the IMPF makes it crystal clear in its report that it believes a new streaming class system has emerged that greatly benefits labels but not publishers (and, by default, songwriters). It has very clear – possibly, depending on where you are in the ecosystem, highly controversial – plans for how to fix that; and we will get to that shortly.

“At IMPF, we believe that the creator of the song should be remunerated as much as the artist,” the report says. “Streaming services ought to be contributing more revenue to songwriters and publishers, and IMPF wants greater collaboration with digital streaming platforms, so everyone can have a better understanding of the real and measurable value of the song.”

“Streaming services ought to be contributing more revenue to songwriters and publishers, and IMPF wants greater collaboration with digital streaming platforms, so everyone can have a better understanding of the real and measurable value of the song.”

– IMPF

The report puts numbers on this growing fissure, saying revenues for CMOs were down 10.7% in 2020 to €8.18 billion but labels saw an 8% growth to €19 billion. This, the IMPF believes, cannot continue. It adds that indie publishers, as they do not have the negotiating heft of bigger publishers, are the most disadvantaged in negotiations with DSPs and it is imperative that they “get their fair share”.

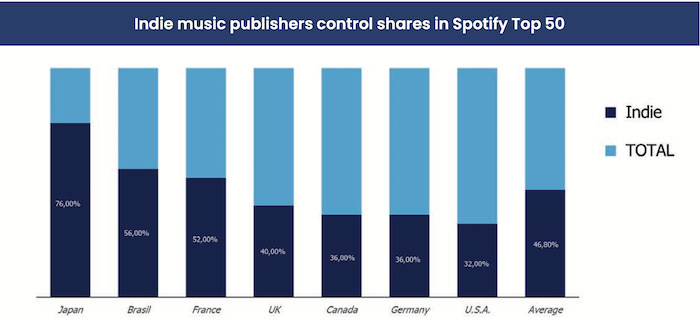

Indies punch above their weight when it comes to global hits

The IMPF looked at the 50 biggest songs on Spotify globally in 2020 and found that the fingerprints of indies were on almost half of them (46.8%) – i.e. there is a writer affiliated with an indie publisher on one of every two of the biggest songs of that year so it is not all just a world sewn up by the majors.

Indies perform even better in certain markets, notably Japan

What 46.8% was the global average for indie publisher involvement in Spotify hits, in certain markets the indies are over-indexing – most notably in France (where 52% of the top 50 songs have an indie publisher involvement) and Brazil (56%), but it leaps to a phenomenal three-quarters (76%) of the top 50 in Japan.

Source: IMPF

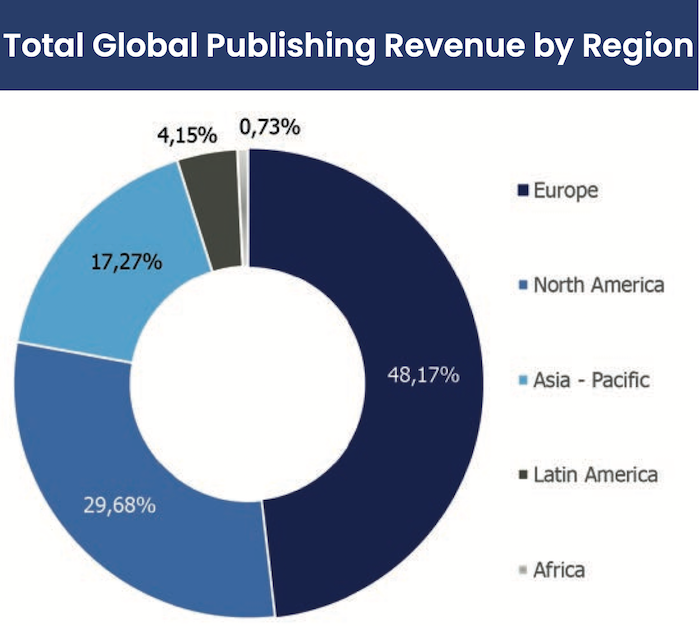

Europe dominates on a regional level while America is preeminent on a country level…

Despite revenues slipping from €4.52 billion in 2019 to €3.96 billion in 2020, Europe remains the dominant region, with a staggering 48.17% share of total global publishing revenues. Europe is significantly ahead of North America (€2.44 billion in 2020 and a 29.68% global share), Asia-Pacific (€1.42 billion and a 17.27% global share), Latin America (€341 million and a 4.15% global share) and Africa (€60 million and a 0.73% global share).

Separating out individual countries, however, the US is dominant with revenues of €2.209 billion in 2020 (up slightly from €2.194 billion in 2019).

Source: IMPF

… but Africa and India are seeing significant developments

Interestingly, the indie publishers are strongest in songs not written in English, showing that outside of the Anglophonic markets independents are performing well. Historically English has been the dominant language of pop and is why the major publishers have such a firm foothold in countries like the US, Canada, the UK and Australia; but as the music business, with global streaming acting as a catalyst, becomes more polyglottic, this dynamic would seem to favour indie publishers more.

Interestingly, the indie publishers are strongest in songs not written in English, showing that outside of the Anglophonic markets independents are performing well.

Related to that is how digital is creating new opportunities for both Africa (as a region) and India.

The IMPF notes that significant organisational and infrastructure changes in Africa – primarily in what it calls its “three main publishing hubs” of Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa – are changing the business. Historically, music publishers in Africa “have been dependent on and closely linked to major record labels”, but this is shifting due to the new power and possibilities tied to digital. There has also been something of a sea change where the importance of publishing is increasingly understood by creators and musicians there.

South Africa – aided enormously by the fact that its major acts tend to remain as residents in the country – has the most advanced publishing system on the continent, but the feeling is that it will offer a template for other African nations to follow.

Indie publishers do well there, with 78% of the top 50 songs in Nigeria in 2020 having some independent publishing involvement, followed by 40% in Kenya and 36% in South Africa (which is understandable given how advanced the majors are there).

In India, the market increased for publishers in 2020, rising 3.9% to €18 million. This may seem small change compared to the dominant global markets, but it is telling for the market’s future that domestic acts are really powering the growth here. IMPF reports that domestic income (which includes performance, mechanical and local synchronisation fees) was up 20.4% to €14 million (i.e. the bulk of the India market) in 2020.

Livestreaming offered a lifeline – but more education around licensing is needed here

With most real-world concerts cancelled for much of the year, there was a boom in livestreaming shows in 2020 (and a concurrent explosion in the number of platforms enabling them to do so). It offered an important way to connect with fans in lockdown but also, and more significantly, became a way to generate revenue from ticketed livestreams.

IMPF says that licences here tend to cover livestreams as they happened but not always for online retransmission (i.e. on-demand plays) which it notes must have mechanical rights covered.

“Educating rightsholders about their rights so that they can fully grasp the benefits offered by news streams of business is key,” it says. “This is one of the priorities of IMPF as we continue to engage with industry bodies to discuss potential new and mutually beneficial approaches to licensing models.”

Streaming rates are the “defining issue” of the day and publishers deserve a bigger share

No doubt provoked by the decline in 2020 as certain key parts of the publishing business model were closed off, the report goes heavy on what it sees as a disparity in how streaming income is divided up between the three key stakeholders – record labels, music publishers and the DSPs themselves.

“The issue of streaming rates is the most important and urgent priority for the wider community to address,” it says. “It is, in fact, the defining issue of where we are at and where we are heading. Rates for publishers have been low from the outset. While record labels are reporting significant increases in revenues from streaming services, the publishing sector (and therefore the songwriters and composers they represent) does not benefit from this growth.”

“While record labels are reporting significant increases in revenues from streaming services, the publishing sector (and therefore the songwriters and composers they represent) does not benefit from this growth.”

– IMPF

It suggests publishers receive around 15% of the money here compared to 55% for record labels and 30% for the streaming services. “This is occurring at a time when the song itself is becoming more valuable as the business moves away from albums towards a track-based model.”

The report is adamant that songwriters, publishers and CMOs need a greater share of digital income. It refers to the cut that DSPs are taking here (revenues they “make off the back of the work of creators”) as now reaching “scandalous proportions”.

It even has a solution to this problem – but how this lands with the rest of the digital music business is certain to cause outrage. Of course, it even coming close to being adopted, even partially, as a transformative solution is far from a given.

Inspired by the arguments coming out of the DCMS inquiry in the UK last year into the economics of streaming, it insists that the sector gets “a complete reset” as soon as possible. Rather than propose that labels lower their cut of streaming and share it with publishers, the IMPF instead questions if DSPs can really justify taking a cut that is twice the size of what publishers get.

“How can we together as the music industry come up with ways to increase the digital pie?” it asks. “We believe that we cannot increase our slice of the digital pie without questioning the current splits – Should DSPs be taking 30%?”

It then asks if, in “the spirit of business cooperation”, the music streaming world as a whole can sit down to “discuss and negotiate fairer licences”.

With the bit firmly between its teeth, the IMPF report closes with a rallying cry to quicken the blood of music publishers and songwriters: “Streaming services need to increase their support for the work of composers and authors by paying up and paying fair!”