Introducing Music Publishing in the Age of the Songwriter, a new report from Synchtank.

Following on from our 2021 publication Drowning in Data, the report examines the fundamental shifts in the music industry in recent years and what they mean for the future of publishing, from new deal types and services that promote transparency and equality to creating more value for songwriters in the digital age.

Through interviews with leading executives and songwriters including Björn Ulvaeus, Carianne Marshall, Jon Platt, Mary Megan Peer, Merck Mercuriadis, and Nile Rodgers, the report delivers the most comprehensive analysis of the music publishing industry from the perspective of those leading it and the songwriters it serves.

The free report will be published in the following 4 parts released on a weekly basis, starting with part 1 below:

- The Evolution of Music Publishing

- Future-Proofing Publishing Services

- Economics, Transparency and Equality

- Digital Drivers of Growth

Introduction

The core principles of the music publishing world – essentially discovering and working songs – have not really shifted in the past century, but the ways in which the business has had to adapt and evolve to market and technological shifts have accelerated in the past two decades.

The digital age for music publishing has been equal parts challenge and opportunity. There are many more places where songs can be worked and publishers have to adapt to new platforms and business models that have emerged in that time.

In parallel with this has been the growing empowerment of songwriters where the old model – built on ownership of rights by publishers – is increasingly unworkable in certain cases. Rather than assigning rights for long periods of time (even for the life of copyright), writers are expecting greater transparency and a wider range of services.

A new generation of companies are stepping forward to offer such terms and the established publishers, both indie and major, are having to recalibrate their offerings accordingly.

This Synchtank report takes the temperature of the industry in 2022, looking at how publishers can (and should) continue to empower creators, offer deals and services that promote greater transparency and equality while utilizing the multiplying range of tools, data sources, platforms and technologies at their disposal to their maximum potential.

We speak to a wide range of executives from all parts of the publishing world – as well as songwriters themselves – to distill the key conversations that are currently happening and how they will shape where, and how, the publishing world will move next.

The business is changing on so many levels – on a licensing level, on an investment level, on a technological level and on a cultural level – and this report takes stock of all the related debates and conversations that are happening right now.

It is not just focused on the present and looks ahead to understand what the new drivers of growth will be, what changes in investment practices, infrastructure and technology will be required for publishers to truly capitalize on new opportunities while continuing to be a compelling, relevant and necessary partner to songwriters.

Drawing on detailed interviews with a wide range of voices – from publishing executives and industry thought leaders through to trade associations, and the creator community (both emerging talents and some of the world’s most renowned songwriters) – to deliver what is the most comprehensive analysis of the music publishing industry from the perspective of those leading it and the songwriters it serves.

Part 1 – The Evolution of Music Publishing

1.1 The music publishing industry in numbers

Pinning an exact number on the value of music publishing globally is somewhat different to the way in which the value of the recorded music business is reported globally by the IFPI and its network of regional affiliates.

While label revenue reporting is centralized and publisher revenue reporting is more disparate, there are still multiple data sources that, when combined, can give us a clearer picture of what publishing revenues are being generated and where they are rising (or falling).

In mid-June 2022, the National Music Publishers’ Association (NMPA) published figures covering US publishing revenue in 2021. The total was $4.7 billion and this was a 15.31% growth from 2020 (and the numbers for 2021 mark the sixth year of growth in a row). In 2021, the pie was split as follows: 51% performance; 25.8% synch; 18.5% mechanical; and 4.7% other

“One of the most important stories from this data,” noted David Israelite, President of NMPA, “is the fact that nearly 30% of the industry’s revenue sources came from places that originally claimed they did not have to license or pay songwriters.”

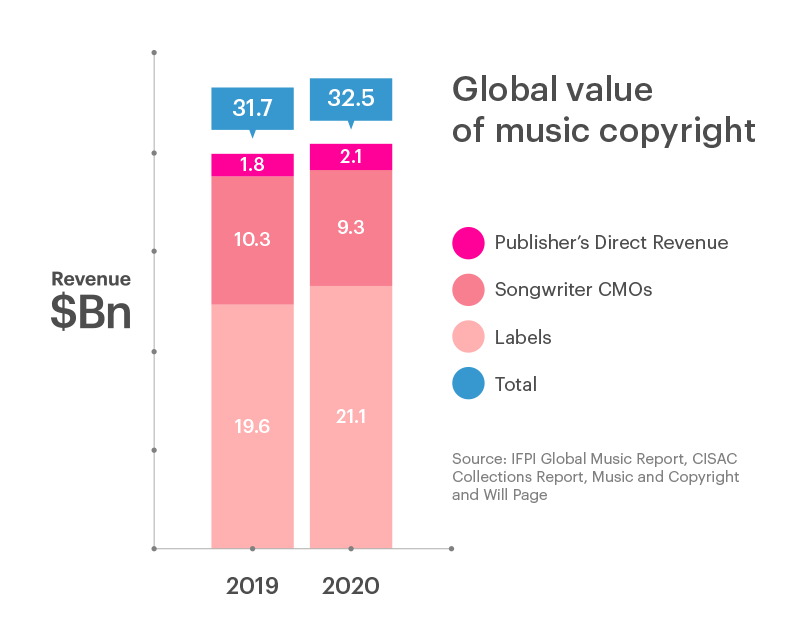

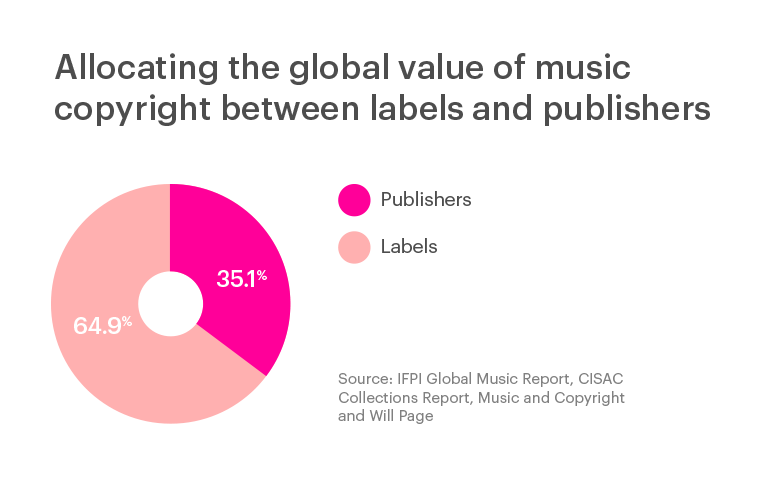

Economist Will Page has, for several years, sought to deliver numbers that capture the entire global value of copyright. He combines data from the annual reports of labels, publishers and CMOs in order to arrive at a broader picture, rather than just focusing on one part.

In late 2021, he reported that music copyright in 2020 was worth $32.5 billion (paralleling this with the $21.6 billion for recorded music reported that same year by IFPI). While that was a 2.7% increase from the previous year, labels benefited more than publishers, according to Page.

“The pandemic stalled growth unevenly,” he wrote. “Streaming was a ‘stay-at-home stock’ that helped labels increase their revenue by $1.5 billion [to a total of $21.1 billion], whereas combined collections for both publishers and their CMOs fell almost $0.7 billion [to a total of $11.4 billion].”

That negative impact of the pandemic on the publishing world was profound as key revenue sources, such as live performances and TV/film productions, were put on hold. That meant that the numbers for 2020 and 2021 were affected in an unprecedented way.

Things are now slowly returning to normal, although different countries are moving at different speeds, meaning that the global picture is naturally going to be affected for some time to come.

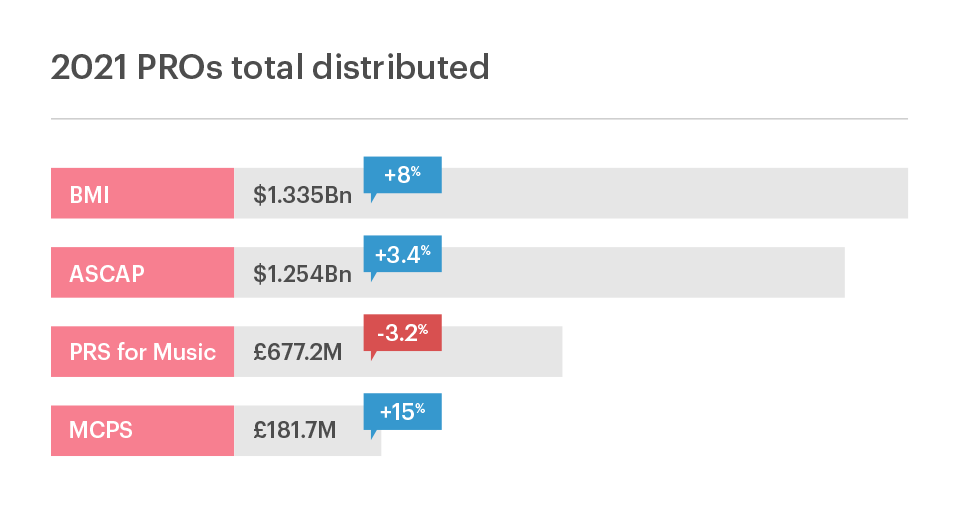

Some solid figures around where the market currently is and where it can move next came in April 2022 when PRS for Music published its numbers for 2021. It reported that revenues increased by 22.4% to £777.1 million, although total distributions actually fell by 3.2%.

When all the different revenue streams were looked at, capturing the push-pull dynamic in the market, the news was a mix of the good and the bad. Online revenues were £267.8 million (a jump of 50% from 2019), but international revenues were down 2.5% to £242.4 million (which PRS explained was down to some markets opening up again but others not opening up quite as quickly).

Public performance revenues were up 59.5% to £137.6 million (as spaces like bars and restaurants opened to the public again) while income from the live music business was down 29.2% to £8 million (which marks a dramatic slump of 85.2% compared to 2019, the last full year before the pandemic hit).

While PRS for Music saw its distribution to members slip by 3.2% from 2020, MCPS saw revenues grow by 15% to £181.7 million. Meanwhile in the US, both ASCAP and BMI saw distributions increase – by 3.4% to $1.25 billion in the case of the former and by 8% to $1.335 billion in the case of the latter.

This parallel dynamic of growth in some areas and decline in others will continue for some time as different Covid responses are still playing out in different markets depending on specific government policies and infection rates.

The net result is that publishers and songwriters have seen wild fluctuations in their income sources and there is ongoing uncertainty with regard to forecasting. This makes the arguments (covered later in this report) about emerging new revenue streams and ongoing campaigning to improve the rates paid to publishers/songwriters all the more pertinent.

For major songwriters with major catalogs, it has been a time of incredible boom and unimaginable opportunity over the past few years. Superstar artists like Bob Dylan, Stevie Nicks, Neil Young, Bruce Springsteen, and Shakira – to name just a handful – have helped usher in the era of the mega-deal, selling all or part of their catalogs for figures running into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

This is also impacting at the mid-level, with increasing competition for catalogs seeing the multiples being offered running to 25x or beyond.

Music Business Worldwide noted that this boom is being driven by whole new entrants who are not music specialists but who smell endless opportunity here. “[T]he giants of the financial world are now really waking up to the modern music business’s true value,” it wrote, “and they’re throwing billions at it.”

Number crunching by MIDiA Research found that $5.3 billion was spent by investors across a range of publicly announced catalog deals last year, marking an 180% increase from the $1.89 billion spent in 2020. That in turn towered over the “mere” $368 million spent in 2019.

Some in the publishing world are warning that more caution is needed here and that people should not get too dazzled by the headline deals that are happening here.

“Valuations right now are sky high and I have absolutely no problem with people selling a catalog that is valued as high as it is at the moment,” says Rupert Skellett, at Beggars Group. “I fully respect and understand writers and artists who are selling their catalog because it’s a fantastic time for them right now. But I don’t know how long it will last, especially if interest rates start moving up eventually to deal with inflation.”

Mike Smith, Global President of Downtown Music Services, says that seller’s remorse among songwriters was a real thing in the business before the current boom, adding that the multiples being offered today might not seem quite as juicy several years down the line.

“People are not feeling ripped off these days because they’re getting some fantastic deals,” he says. “But maybe in 20 years’ time they may look back and go, ‘Oh my God! Why did I sell my copyright for that much? I would’ve been much better off holding onto it.’”

Tim Parry, CEO of Big Life Management, is not convinced the major publishers constantly buying up catalogs is a good idea, especially if the acquisition drive is more about quickly growing market share than doing something creative and interesting with the assets when they get them.

“My opinion of the major publishers isn’t that great [when acquiring catalogs],” he argues. “I don’t think they’re that good at what they do because they’ve literally got too much to deal with. So if they’re buying someone’s catalog, what are they really going to do? I imagine they’ll be fairly passive [with exploiting bought catalogs].”

He adds, “Some publishers don’t know what [catalogs] they’ve got. I know this because when we sold our catalog [to a major], for a while they didn’t think they represented our catalog. When it came to a sync request, they denied they repped it. It’s quite inefficient because they’ve got millions of songs [so it’s hard to manage].”

A select few are benefitting enormously from this current bonanza, but smaller music publishers are arguing that the playing field could be a lot more even.

In December 2021, the Independent Music Publishers International Forum issued its year-end report and argued that the impact of the pandemic and the uneven distribution of streaming income was hitting indie publishers hardest, who make up over a quarter (28% of the global market.

In the US in 2021, arguments around the proposed Copyright Royalty Board (CRB) rates, covering 2023 into 2027, erupted into very public disputes. Some DSPs were pushing hard for a freeze on the current rates of 15.1%, or even a reduction, while the National Music Publishers’ Association was insisting on an increase to 20%.

This, it should be pointed out, relates to CRB IV and the previous ruling (CRB III) is still being contested. Spotify, Amazon, Google and Pandora have spent several years appealing the CRB ruling, which saw the rate rise from 10.5% to 15.1%, although publishers are still being paid at the lower rate while the appeal plays out. Warner Chappell called this “an appallingly low rate” in a letter to its members in February 2022. (Apple did not appeal the CRB rate for 2018-2022 but is pushing for a rate of 10.5% for 2023-2027 if the judge sides with the other companies who are appealing that 2018-2022 rate.)

To put the economic implications of all this in context, David Israelite, President of NMPA, noted that 96% of US publisher income in 2021 came from “the same five companies that are fighting to cut songwriter rates in the CRB process: Amazon, Spotify, Apple, Google, and Pandora”. These five companies essentially are the market and their push for a lower rate would dramatically cut future earnings for publishers and songwriters.

However, the mechanical rate increase in May 2022 – from 9.1 cents per track for physical records to 12 cents per track – was a clear win for songwriters and publishers.

Despite the difficulties caused by the pandemic – and their impact on the bottom line of everyone in the publishing world – music publishing is worth more today than it ever has been.

This is down to a multitude of factors, but, on a macro level, the most significant are that the publishing business is more global than ever before (as more markets flex their muscles and offer whole new opportunities for the monetization of music rights) and there are far more licensing outlets than ever before (from livestreaming, short-form video platforms like TikTok, social platforms like Instagram and Facebook, gaming, the metaverse, Web3 and fitness/wellness).

The fact that publishing has diversified so much and held steady in the pandemic is proof of both its resilience and its forward propulsion by finding new ways of licensing and monetizing music.

Collections fell less than projected as a result of Covid (back when the worst-case scenarios were being written in the opening half of 2020). Given the reporting lag times here, however, the full effect may not be known until the end of 2022 or later when detailed numbers from a variety of organizers and publishers come through.

This is a pivotal moment for the music publishing sector: it has weathered the challenges of the pandemic and is focused on opening up new markets and new market opportunities.

While there are many more ways for publishers and songwriters to make money – be that through licensing their catalogs or even selling them – it does not follow that legacy problems no longer need to be resolved. The ongoing battles over streaming rates, for example, and the wider regulatory challenges here show that fixing the existing models is of equal importance to finding the models of the future.

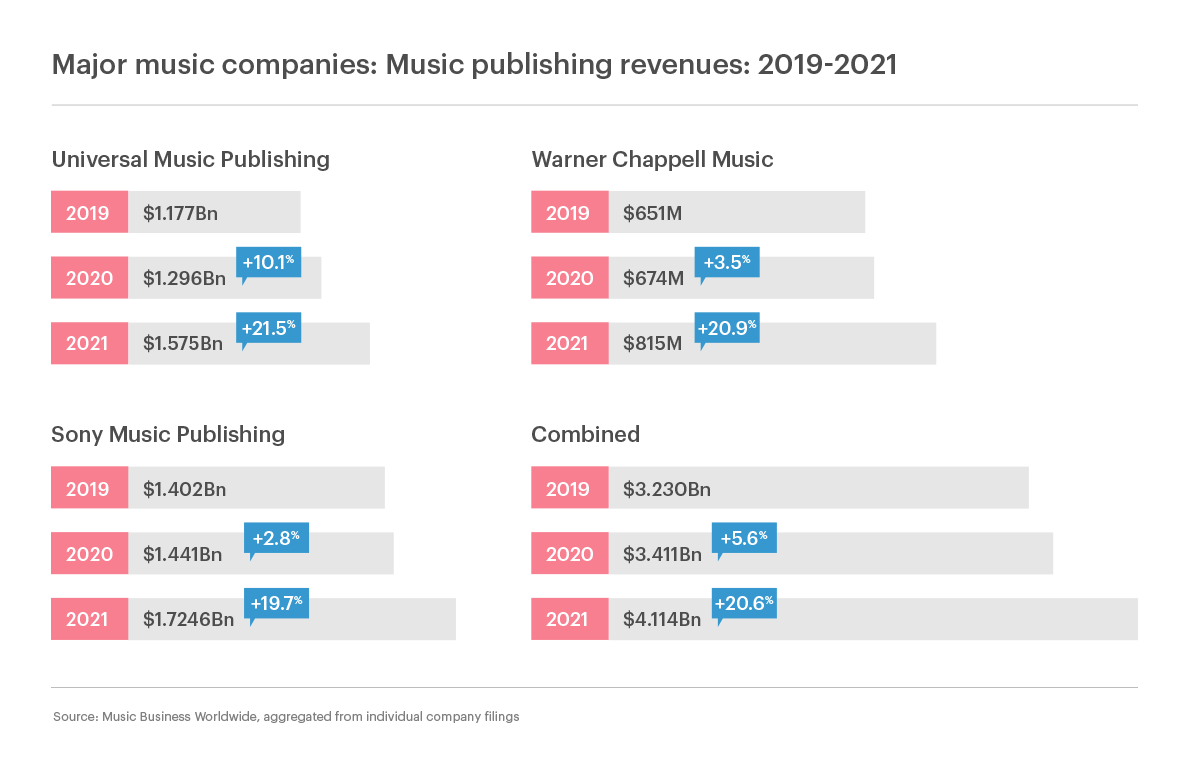

Majors’ publishing revenue: 2019-2021

Digital growth from streaming, new digital deals and settlements have helped to offset decline in performance and mechanical revenue caused by the pandemic.

Key takeaways: combined major publishing revenues climbed 20.6% to $4.1 billion in CY 2021. The major publishers generated over $4 billion in CY 2021 and almost half a million dollars per hour.

1.2 The changing landscape of music publishing

Like all businesses should be, music publishing is in a necessary state of flux. This is essential for its future growth and survival.

There are a multitude of ways it is changing and we have spoken to key players across all parts of the business to understand what changes they are seeing happen as well as the changes they would like to see happen in the coming years.

There have been accelerated acquisitions in recent years – not just the blockbuster catalogs of individual writers, but also entire publishing companies, showing there is an enormous amount of investor faith in the publishing sector as entirely new ways to monetize music are coming on stream and proving their worth.

We can arguably trace this most recent trend towards accelerated consolidation back to 2012 when Terra Firma lost control of EMI and its EMI Music Publishing arm was acquired by a consortium led by Sony (with Sony fully acquiring EMI Music publishing in 2018).

Other notable deals since then include Kobalt buying Songs Music Publishing in 2017, Downtown buying Good Soldier Songs in 2000 and then Concord buying Downtown’s publishing copyrights in 2021, BMG partnering with investment company KKR in 2021 to buy up catalogs and then KKR/Dundee Partners buying Kobalt’s KMR Music Royalties II portfolio later that same year.

The arrival of Kobalt in 2000 changed the rules of engagement here by placing technology as central to its offering, allowing swifter and more transparent processing of payments.

“We have created transparency,” asserts Willard Ahdritz, founder of Kobalt, on his company’s impact. “We created one global platform and introduced technology […] We introduced a portal that you could search by work, by copyright, by recordings, at source, over time. A real-time database, not just the last six months. We introduced relationship databases. There was no relationship between the songs and the recordings. We linked everything together and that was that full global transparent tool […] So far, I have not seen anyone who is able to do that on a global scale.”

This bold claim is backed up by others in the industry.

“We signed [with] Badly Drawn Boy back in 2000, he was one of the first writers they [Kobalt] signed and he’s still with them,” says Tim Parry, CEO of Big Life Management. “They really did change the rules. It went from most publishers accounting twice a year to quarterly accounting. They’re a tech-based company, so everyone else had to catch up with them. Everyone else is [now] doing the same things as Kobalt did; the deals [are more] short term.”

Michelle Lewis – singer, songwriter, composer, and music creators’ rights advocate. Co-founder of SONA (Songwriters of North America) – concurs.

“I think Kobalt changed the game on transparent administration,” she says. “Being able to look at your statements on demand, that forced everybody to be able to [offer something similar]. Now we have these portals, we just go into our dashboards – everyone from our PROs to our publishers – and we see exactly what money’s there. I think that was a dramatic shift.”

Scale in publishing is one thing, but there is a whole other well-established ecosystem that exists outside of the purview of the biggest players that also allows writers to compete on a similar footing. Much of this leveling of the playing field is down to the impact of digital.

“The tradition of an old-school deal with a major is really not so important for up-and-coming artists, because of the impact of not only the internet but also the DSPs,” proposes Lawson Higgins, Vice President of Creative at The Royalty Network.

Golnar Khosrowshahi, CEO and founder of Reservoir Media Management, explains the current shape of the market in terms of a triptych.

“I think it has become abundantly clear that there are three types of publishers today,” she suggests. “I wouldn’t even call them publishers: three types of companies that have, or are, investing in publishing rights. The first is publishers like us, independent publishers who have a platform. Second is financial investors who don’t have a platform and are just looking at this as an investment. And then you have the majors. That delineation has become very clear.”

The domino effect of all these shifts has been that every major player has had to up their game and provide data tools and more transparent accounting to writers on their books (this is covered in more detail in Section 2 and Section 3).

“We’re very focused on improving data accuracy and transparency,” asserts Antony Bebawi, President of Global Digital at Sony Music Publishing. “We’re doing everything we can to make sure our songwriters are getting paid efficiently and accurately. In today’s environment, it’s important to understand that there isn’t one specific challenge or problem and there isn’t one solution or one initiative that will fix or address all of the challenges we face.”

Some, however, are not so convinced that all the talk today about transparency is anything more than that – just talk.

“There are concerns about transparency and access to the right level of information that is actually made available to creators and their managers,” argues Graham Davies, CEO of The Ivors Academy. “I think there are concerns over how much access to information creators get. They might get information on the royalties that they’re being paid, but they’re not necessarily getting the information on the royalties they’re not being paid or how parties representing their interests are being paid.”

A new generation of companies like Songtrust, Sentric (recently acquired by Utopia) and Ditto have all stepped forward here to cater for emerging songwriters by developing self-serve tools and a range of bolt-on solutions for them without having to sign up to a traditional deal.

“We offer low-commitment, 30-day rolling contracts for specific compositions, but we offer a completely personalized service,” says Tom Weller, Managing Director of Ditto Music Publishing & Ditto Plus. “We conduct a full copyright audit of everything that’s assigned to us to ensure it’s registered correctly around the world with no duplications or disputes; our sync team spends time really familiarizing themselves with the music and puts together a targeted sync strategy for every release; and we invest a lot of time in ensuring that every share of every track is easily clearable.”

He adds, “We also offer a neighboring rights administration service to Ditto Plus clients. We just want to make it as easy as possible for our clients to collect their royalties by allowing them to have all of their rights administered centrally.”

Molly Neuman, President of Songtrust, says new deal models are essential as companies must respond to changing demands and expectations in the songwriting world.

“I think traditional publishing deals historically have been somewhat restrictive in terms of the ownership of the works, whether it’s in that term or in perpetuity,” she says. “I find it a little bit challenging for someone who is 15 to enter into a long-term restrictive deal for multiple cycles of their career in all likelihood.”

While new entrants are coming in with whole new ways of working, the majors insist that they too are moving with the times.

“At Warner Chappell, we’ve evolved to a place where we can do every type of publishing deal and don’t have to limit ourselves to one way of working,” says Guy Moot, the company’s co-chair and CEO. “Whether it’s acquiring a catalog or helping songwriters extract more value from their songs, we have a wide offering of support services and the expertise to truly support songwriters and grow their careers in a meaningful way.”

Marc Cimino, Chief Operating Officer at Universal Music Publishing Group, explains how his company is also ensuring that the writer is at the very heart of what they are doing.

“Jody [Gerson] and I came into this company emphasizing that we are here to do everything we can to benefit our songwriters,” he says. “That is the mantra that we repeat to ourselves daily and it is our guidepost in every single decision we make up and down the company. It’s a lot more fun to be aligned with talent. With that as our ethos, our company has done a great job of making sure that the creative community knows it and we have been fortunate enough to have such incredible talent entrust us to be their publishing partners.”

This all requires huge investment in software, staff and infrastructure. That can come from external investment and partnerships (such as BMG and KKR) or from companies selling up part of their business to double down on other parts (seen most explicitly in Downtown selling its owned assets to Concord in early 2021 to focus on the publishing administration arm of its business).

Those coming with a fintech and capital investment approach to the publishing world feel there should be a bifurcation in the sector based around expertise and skills.

“Publishers and other service providers should look to provide services not capital, or understand the old model is broken,” proposes Stephen Duval, Chief Executive Officer of Empowerment IP Capital. “If they do provide capital, it needs to be separated from the services. The world is changing and there is significant transparency now through data and people using the old model will not exist in time.”

Mark Mulligan, MD of MIDiA Research, suggests these new structural changes will force through a reevaluation of the publishing sector and how we understand how different parts of it work.

“In some ways I think it’s almost like the business of songs rather than the songs business, because, with the financialization of music as an asset class, what we’ve essentially got is people valuing catalogs as a financial asset more than as a cultural asset,” he says. “We saw the volume of M&A transactions last year [experiencing] far faster growth than the growth in the recorded music market or the publishing market. The value is going up as well. Essentially the M&A part of the music business is becoming decoupled from the actual music business itself.”

The global nature of the digital business means that companies have to scale up in their operations and technologies to be able to operate swiftly and effectively at this global level. They are also investing in much more than just publishing copyrights, with Primary Wave, for example, moving to buy up masters as well as name/image/likeness rights in certain instances (covered in more detail in Section 2).

There has also been a boom in neighboring rights, with a range of companies – among them peermusic, Round Hill and BMG – setting up dedicated divisions for this and majors like Sony Music Publishing setting up a neighboring rights arm (and then acquiring Kobalt Neighboring Rights). (This is covered in more detail in Section 2.)

Ultimately publishers are in the business of songwriter development and securing as much exploitation as possible to maximize revenues for songwriters, although it is increasingly multifaceted today, something this report will explore in greater depth.

1.3 The evolution of the songwriter and their needs

Songwriting today is evolving just as the market itself is evolving and songwriters are increasingly polymathic as the lines become more and more blurred between artists/songwriters/producers. The idea of a pure play songwriter still exists, of course, but many songwriters are having to become multi-disciplinarians.

“I think there is a huge potential in the future that artists and songwriters will have a firmer hold on their own careers than they have previously,” says Björn Ulvaeus, songwriter, member of ABBA, co-founder of Session and President of CISAC. “I think more and more of them are becoming entrepreneurs at the same time due to the fact that they have to be everywhere, they have to do everything in quite a different way than it was before when you were in your artist role. Now it seems it’s all wrapped into one and it has to be.”

Out of this complex and shifting market, a new generation of songwriters is emerging. They are increasingly entrepreneurial and autonomous – more empowered to do things on their own terms, expecting to have more options open to them and experiencing greater leverage in the market.

“I believe songwriters have always been empowered, but I believe they are using their voices now more than ever before,” says Jon Platt, Chairman & CEO of Sony Music Publishing. “Songwriters and composers are being vocal about what they want in their careers and in their lives. I think that’s a good thing. I believe that any day a songwriter is using their voice is a good day for this industry. Songwriters own 100% of their career on day one. On day one [of their careers], they have the opportunity to choose how to move forward with their careers. That is very important.”

Josh Oliver (aka Jolé), an emerging singer and songwriter, also takes the line that songwriters today are wrestling back more control over their careers and the types of deals they sign.

“I would say [songwriters are more empowered than ever] because I think there are a lot more resources now to create an income,” he proposes. “I think the biggest thing in the past was probably the income that you got from music and you had to sign to publishers or labels in order to move forward with your career. Whereas now there are a lot more opportunities to do that yourself and have your own control over it.”

This new breed of songwriter has a much deeper understanding of the value of rights/ownership than they used to have in the recent past and this is reflected in new approaches (e.g. flipping catalogs and using the capital to fund other parts of their business).

As Mike Smith, Global President of Downtown Music Services, says,” You’re seeing a very different approach from a lot of young songwriters where they go into the songwriting business, they have a five-year period of writing a lot of songs and having a lot of chart success and making a lot of money. Essentially those copyrights are valuable and they flip them in the same way that somebody would flip a business. And so that’s a relatively new approach. I think it reflects how entrepreneurship is a much bigger part of young people’s lives these days than it was in the past and how songwriters are becoming more entrepreneurial.”

While there is much cause here for utopianism, the convoluted world of music publishing can still leave songwriters confused and frustrated. Music publishers have a duty to provide transparency and education around the true value of publishing, how deals work and how the money flows.

Platt says Sony Music Publishing has a clear obligation to ensure its writers are educated about the complexities of the business and how it will change in the future.

“If songwriters and composers aren’t understanding how the business operates, it is our responsibility to help them understand,” he says. “Empowering songwriters and composers is very important to us and I appreciate how they are being more vocal.”

There can be a lack of awareness around the value of publishing for emerging songwriters in particular. Companies such as Songtrust are proactively educating songwriters and, in the process, demystifying how things work for this creator class.

Terms have, in many cases, shifted from the 50:50 life of copyright deals that defined the past and instead splits like 80:20 and co-publishing deals are becoming standard. Within this, deal terms and reversion terms are getting shorter. Admin deals are becoming more common here, a powerful trend that is covered in greater detail in Section 2.

“In the past, an aspiring songwriter would do a 50:50, life of copyright deal with a music publisher – and that writer would be grateful because they knew they were getting their songs worked,” notes Mike Smith, Global President of Downtown Music Services. “Slowly we moved towards a more equitable business whereby you’re looking at 80:20 splits in favor of the writer and retention periods went from life of copyright to 25 years to 15 years. And now they tend to be in the 10-to-15-year period.”

Larry Mestel, founder and CEO of Primary Wave, says that shorter deal terms being tabled by writers and their legal representatives run counter to the philosophy his company is built on – namely being a partner for the long haul and displaying commitment that way.

“We’re seeing lawyers asking for 10-year reversion rights or 15-year reversion rights, not waiting for the end of a normal co-publishing term,” he says. “There have been very bold asks for new songwriters because they want to get their songs back as soon as possible. That’s not a game that we play. We’re not interested in doing deals where we are not long-term partners. The majors do those deals. I think you’ve got to look at the return on your investment as much as how successful a writer can be.”

He continues, “If we’re going to put all the time and effort, marketing support and leverage of our team behind something, we want to be partners. We don’t want to, say in six or seven years, have to worry that we’re losing the rights. That’s just not a business we want to be in, but that’s what’s happening. It’s shifting towards writers doing deals where they get their catalogs back sooner rather than later.”

Counter to this argument from Mestel is the argument that shorter terms would actually engender a culture of greater competition for rights and those representing them for a set period will be compelled to work them harder and more creatively.

“We’re campaigning at the moment to get more of the US model where contracts have a reversion clause to enable the creator to renegotiate their contract after, say, 20 years,” explains Graham Davies, CEO of The Ivors Academy. “I think that shorter contracts or contracts with reversion rights encourage performance and competition.”

He adds, “Not exploiting a copyright after a period of time is also unfair and the basis of what an exploitation is should be meaningful. If the publisher no longer has any interest in the works they are publishing they should return them to the creator to enable them to do something with them.”

Tricky Stewart, multi-Grammy Award winning songwriter, producer, and composer; as well as the owner of 2 recording studios and Partner and Co-Founder of the independent record label RZ3 Recordings, is firmly against the outright copyright ownership model that the business was built on.

“Every other business is created to have an exit strategy – and music is the only one where people hold onto your asset forever until it depreciates,” he says. “And then you can’t get the multiples for it. That’s not really how business works.”

There is some skepticism about the smaller and shorter deals as, counter to the logic of the boutique approach, there could be less of a commitment from the publisher to work their investment. If they are not on the hook for a lot of money, runs the argument, they will not be quite so forthright in how they work and seek to monetize that songwriter’s music.

“Even though it was me who negotiated the shorter term and smaller advance term, I now regret that a bit as it may mean the publisher doesn’t work as hard for my music to try and recoup their investment,” says Milo Evans, an emerging songwriter and artist. “It also means it’ll be harder for me to recoup that advance.”

He reflects on how things could have been different.

“If I were to negotiate a new deal now, I may ask for annual guarantees of income, number of sync placements or similar,” he proposes. “All with the view that, if the publisher isn’t working hard enough for my music, then there is a get-out clause.”

Tiffany Red, artist, songwriter, producer and founder/Director of The 100 Percenters, says having been through the system means you have 20/20 vision on what you would do differently a second time around.

“If I were ever to do a deal again, it would be simple,” she says. “Two- or three-year deal with no MDRC [minimum delivery release commitments] that is complete whether it’s recouped or not after that two or three years. I feel like that’s more than fair. It’s the publishing company’s job to exploit my copyrights, so the deal being recouped is just as much on them as it is on me.”

There is a dizzying amount of choice now for songwriters as to what type of company they want to work with and what shape of deal they can push for. Negotiations and options here are becoming incrementally more convoluted.

“A songwriter’s decision is, and has always been, based on a lot of factors to enter into a different agreement – a traditional songwriter agreement, a co-publishing administration, a joint venture, any other type of arrangement,” explains Mary Megan Peer, CEO of peermusic. “It depends on where they are in their career and what they’re seeking in a publisher. Co-publishing deals with very long retentions were once really the standard. Today, retention periods, re-assignment of administration rights, and assignability of income streams are increasingly highly negotiated terms.”

With songwriters’ demands increasing and their expectations shifting, the onus will be on publishers to keep re-inventing the deal. The more new entrants there are here (offering new deal terms and greater flexibility/autonomy), the more the bar is raised.

As such, publishers must be able to offer a flexible range of deals and be less headstrong about rights ownership on a long-term basis. They will be expected to offer whole suites of services to support the multitude of paths that songwriters wish to take.

The types of deals songwriters are looking for depends on a range of factors.

“I think traditional publishing deals historically have been somewhat restrictive in terms of the ownership of the works, whether it’s in that term or in perpetuity,” says Molly Neuman, President of Songtrust. “[But] I think that there’s still a lot of work to do in terms of having that represent actual change and actual progress in how the royalties are allocated, distributed, calculated, and ultimately received by this [new creator] class.”

The majors have enormous financial resources and powerful infrastructures, but indies can become more boutique and flexible.

In an era of quick hits, songwriters are increasingly looking for long-term development and relationships – essentially seeking a partnership approach (although this is not always easy with lots of M&A activity happening in the space and buyers looking for catalogs that are locked down before they pay up).

“This is all relationship based and investing in those relationships with clients is a way to futureproof the business and to also justify your raison d’être,” says Golnar Khosrowshahi, CEO and founder of Reservoir Media Management. “It’s a very, very important part of the business for me.”

Writer and producer Tricky Stewart concurs. “Everything with me is relationship based,” he says. “I don’t go places for checks.”

Increasingly a number of songwriters are prioritizing a boutique approach – where they are less likely to get lost in the machine – over and above a big-money deal with a larger player. Others, of course, will want the big check, but may also be looking for something more tailored to their needs and future career.

“I think big advances are popular with every songwriter, but what songwriters are also looking for, particularly with smaller independents, are partnerships,” suggests Helienne Lindvall, songwriter and President of the European Composer & Songwriter Alliance. “We want our publisher to know our catalog, know what we’re about, put us in the right rooms with other artists and songwriters that can further our career, and also to know the catalog well enough to be able to get good syncs.”

As more and more artists (who are also songwriters) opt for distribution-only deals on the label side, a publisher’s role is actually becoming more important, especially at the earliest stages of their careers.

Related to this, publishing and recorded rights do not always have to be welded together in deals. In the early 2000s, the major labels, most significantly Warner Music Group, were pushing for 360-degree deals with new acts, seeking to sign them to their recorded music arm and their publishing arm (as well as taking a share of live, merchandise and so on).

While some independent labels also do this, others feel that it might not be the best route to pursue.

“I am aware of some record companies who insist on always picking up publishing when they pick up the records and that’s not something we [Beggars Group] do,” says Beggar Group’s Rupert Skellett. “I don’t think that it’s necessarily healthy in all scenarios. You have to have a good feeling about the people you’re going to be working with, because it’s a really important part of your career; so make sure the relationships are right.”

Ross Golan, songwriter, record producer, playwright and host of And the Writer Is… podcast, says writers need to have a clear vision of what type of career they want before they enter the industry. Within this, he feels they need to take more responsibility for the direction (good or bad) their career takes.

“The challenges in this industry are pretty deep and a lot of being a songwriter depends on what your objectives are,” he proposes. “If you want to be an artist, if you want to be a songwriter, if you want to be a songwriter that makes a living at it […] A lot of times the system is blamed for the lack of financial stability rather than the creatives and what their objectives are.”

Publishing is first and foremost a relationship business, but it is now essential for publishers to offer a compelling and competitive range of services that are enhanced by technology and data.

Publishing companies need to be financially flexible for their writers. This was all laid bare during the pandemic where writers were seeing whole areas of their business closed off and revenue streams dry up overnight. Speed of payment is one thing, but understanding that writers might be struggling is something publishers need to be attuned to, argues Mary Megan Peer, CEO of peermusic.

“We really focus on individual relationships,” she says. “We generally give writers advances when they ask. We have flexible payment options when necessary since we really focus on customizing ourselves to the writer’s needs.”

Songwriters, however, are not always convinced these changes in the business are happening fast enough or if they are really benefiting from them.

“Songwriters are at the bottom of the totem pole at the moment,” claims Helienne Lindvall. “Solving all of these issues will not happen overnight, and songwriters are really, really struggling right now – in particular new songwriters who don’t have a catalog with revenue ticking over and don’t have the really big hits.”

Graham Davies, CEO of The Ivors Academy, believes there should be a de-emphasis on owning rights in perpetuity and instead would rather welcome a doubling down on providing better services for writers.

“I think publishers should move away from acquiring rights forever and instead offer a range of flexible services that enable songwriters and composers to get the money [due to them] – and support services that songwriters need at different points in their career,” he says.

Michelle Lewis, co-founder of SONA, strongly agrees. “I think these companies [should] view themselves more as tech companies and as rights management companies, rather than property owners,” she says. “Maybe [they should be a hybrid of property owner, property management, tech management and tech ownership. I think those are the ones that will flourish in the future, as long as they don’t forgo human relationships.”

The industry is entering a new era of deals, where technology, transparency, and artist-focused services are the norm and not an afterthought. This is only going to snowball further.

Check out part two, Future-Proofing Publishing Services, which will be available on 28th June, and will examine the growing suite of services that publishers must offer to support songwriters today.

Subscribe to our newsletter to recieve the next instalments of the report in your inbox each week.

With huge thanks to the following report contributors:

Adam Betts (Colossal Squid), Antony Bebawi (Sony Music Publishing), Björn Ulvaeus (ABBA, Session, CISAC), Brontë Jane (Third Side Music), Carianne Marshall (Warner Chappell Music), Carter Armstrong (peermusic), Chris Cass (Synchtank), Colin Young (C.C. Young & Co.), Craig Currier (peermusic), David Israelite (National Music Publishers Association), Golnar Khosrowshahi (Reservoir Media Management), Graham Davies (The Ivors Academy), Guy Moot (Warner Chappell Music), Helienne Lindvall (European Composer & Songwriter Alliance), Janet Kirker (Synchtank), Jin Jin, John Vella (Tenderfoot), Jon Platt (Sony Music Publishing), Josh Oliver (Jolé), Justin Tranter, Larry Mestel (Primary Wave Music), Lauren Faith, Lawson Higgins (The Royalty Network), Marc Cimino (Universal Music Publishing Group), Mark Mulligan (MIDiA Research), Mary Megan Peer (peermusic), Merck Mercuriadis (Hipgnosis), Michelle Arkuski (She Is The Music), Michelle Lewis (SONA), Mike Smith (Downtown Music Services), Milo Evans, Molly Neuman (Songtrust), Nancy Matalon (Spirit Music Group), Niclas Molinder (Session), Nile Rodgers, Rob Dippold (Primary Wave Music), Ross Golan, Rupert Skellett (Beggars), Sara Lord (Concord Music Publishing), Shauni Caballero (The Go 2 Agency), Stephen Duval (Empowerment IP Capital), Tayla Parx, Tiffany Red (The 100 Percenters), Tim Parry (Big Life Management), Tom Weller (Ditto), Tricky Stewart, Vickie Nauman (CrossBorderWorks), Willard Ahdritz (Kobalt Music Group)