This is the first in a series where we highlight some of the key issues addressed in Synchtank’s new Drowning in Data report. The report examines the challenges music publishers are facing with regards to rights, royalties and payments in the digital age.

There was a lot resting on the shoulders of the Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC) even before it rolled into operation at the start of the year (following the Music Modernization Act being signed into law in late 2018). For European rightsowners and industry bodies, the painful memory of the implosion of the Global Repertoire Database (GRD) in 2014 after just four years still wraps around everything like a miasma of failure. There has, however, been immense good will behind the MLC and a desire to learn from – and to resolve – the mistakes of the recent past.

In April came the first real proof of concept of the MLC system in operation when it published the financial results from its first month in operation. “The distribution process started in February when DSPs began reporting their streaming and download usage data for January 2021 to The MLC,” it stated. “The royalty pool for all usage data reported to The MLC totaled more than $53 million when calculated at the applicable statutory rates.”

It continued, “The MLC was then able to match approximately 80 percent of the royalties reported to musical works registered in its public database, a figure that is in line with industry benchmarks for initial matching results.”

It added more financial meat to the licensing bones by stating that, of the $53 million reported, some $24 million in matched royalties was paid to its members while $16.4 million was “pending distribution”, including $11 million that it “has not yet been able to match to the musical works in its public database”.

No one expected perfection straight out of the gates – this will be a protracted process over the coming years – but this is surely an encouraging start. The fact the MLC was swift to make its numbers public also augurs well for its ongoing development.

The long-term hope is that it will prove a real catalyst for change and that its efforts will synchronise with others in the royalties collections and tracking business, most significantly the launch at the end of last year of Songview (a joint initiative between ASCAP and BMI which describes itself as “a comprehensive data platform that provides music users with an authoritative view of copyright ownership and administration shares in the vast majority of music licensed in the United States”).

There are still many legacy issues and problems to address here that are not going to disappear overnight – so we must temper our euphoria for now.

Henry Marsden is founder and CEO of Creatr, a new platform soon to launch in beta that will connect creators and give them full visibility on where their music is being used. (Its strap line is: “Regain control of your rights in the music industry, be empowered through your data and get the credit you deserve from within your community.”)

“Getting to a state where we trust a global data set thus depends on transparency and interoperability – two challenges themselves to achieve at scale in a competitive landscape.”

– Henry Marsden, Creatr

“There’s a complex tapestry of data issues at play eating into the value of copyright globally, a lot of which stem from historic national-level blanket licensing,” he says of the ongoing challenges here. “No one in particular is to blame, but any meaningful solutions will require significant collaborative buy-in, which the GRDB showed is difficult to achieve in practice. No solution can claim to be a ‘single source of truth’, as much as we would all like one, without wide acceptance of that fact. In much the same way that the value in currency is built on trust in that currency, the value in data is built off our combined trust in it. Getting to a state where we trust a global data set thus depends on transparency and interoperability – two challenges themselves to achieve at scale in a competitive landscape.”

As outlined in Synchtank’s new Drowning In Data report, the evolving nature of data and data payment processes is becoming increasingly complex. Some of the biggest challenges to now deal with include:

- the impact of the “industrialisation” of modern songwriting where hit songs have an average of 5+ writers (and, as a result, multiple publishers representing different shares of the rights);

- the ongoing fragmentation of rights whereby songs come with different ownership or control shares (which can vary from territory to territory);

- a growing number of income sources;

- different royalty rates and payment terms;

- different national copyright regulations;

- the impact of the securitisation and commodification of copyright royalties whereby an increasing number of parties need to be reported to and paid.

“Collaboration is on the rise which brings with it more co-controllers of every song,” says Marsden of some of the major complications here. “More entities to share and register data. More entities making data registration errors. More sub-publishing chains to pass data onto. The exact same set of data regarding a specific song is re-registered at society level many, many times over globally – an absurd thought given our digitally interconnected age.”

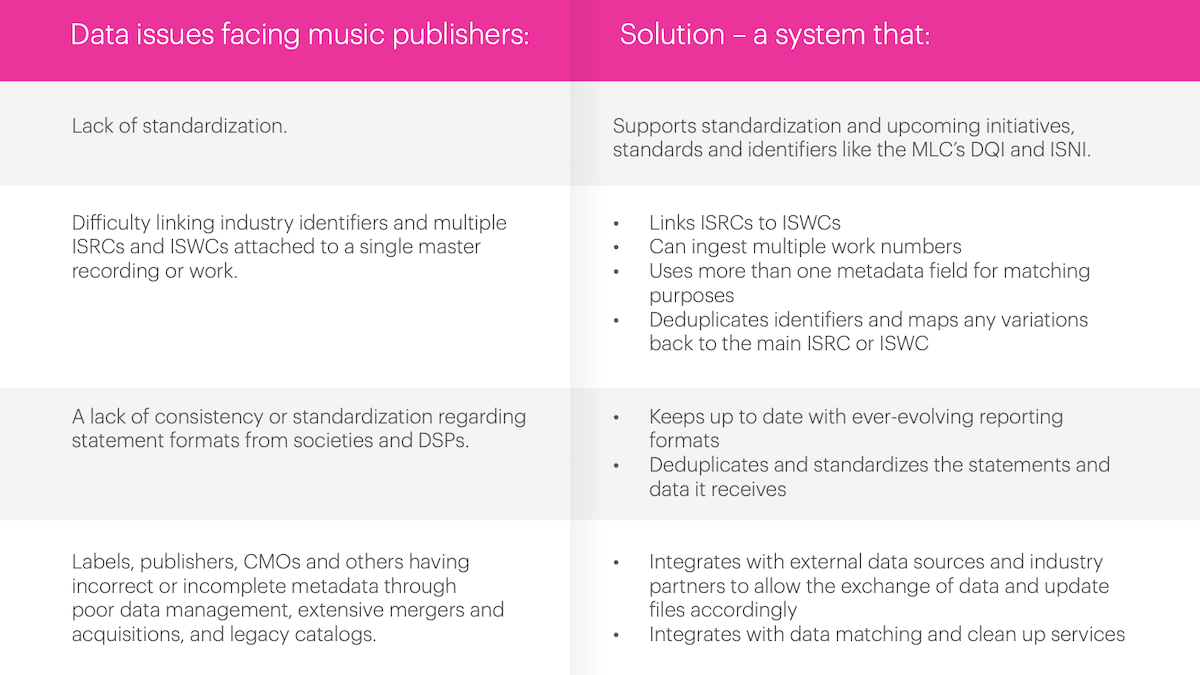

Ultimately, the lack of standardisation across the music ecosystem is a huge concern, with data matching problems meaning the potential loss of millions of dollars in revenue.

Source: Synchtank’s Drowning in Data report

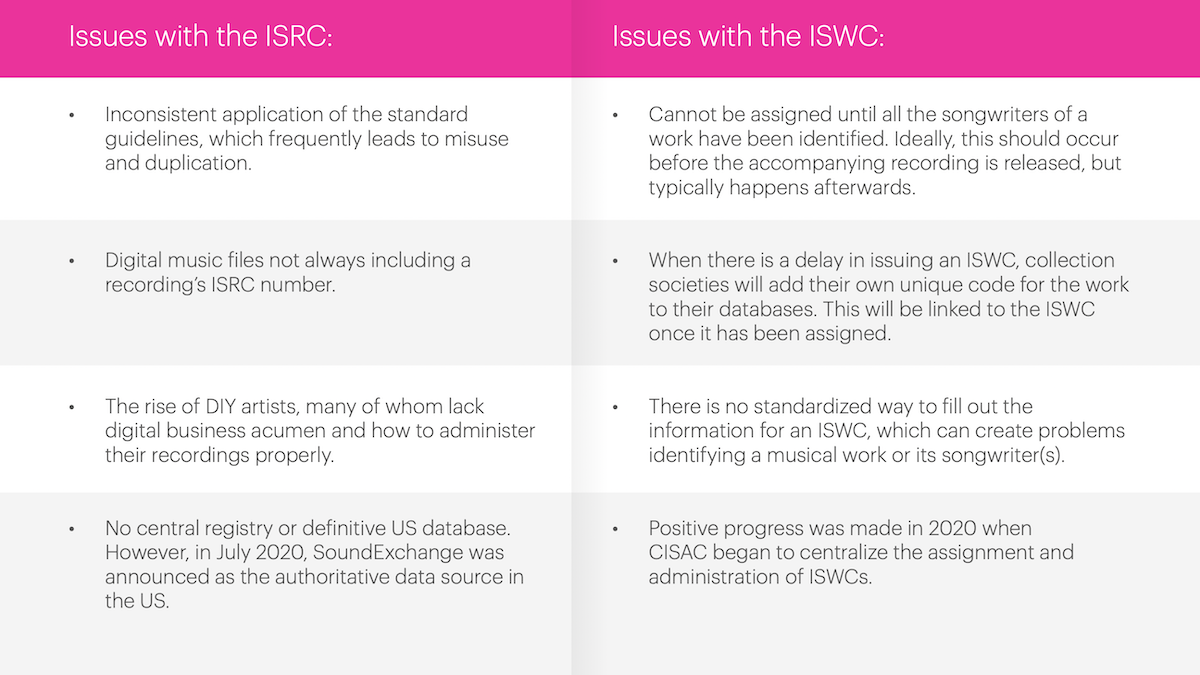

The development of the International Standard Recording Code (ISRC) and the International Standard Musical Work Code (ISWC) are some of the attempts to patch the data leaks here, but both come with their own limitations or problems.

For ISRC these include inconsistent application of the standard guidelines (leading to misuse and duplication), digital music files not always including a recording’s ISRC number and the growing class of DIY acts who do not always administer their recordings properly.

For ISWC these include the fact they cannot be assigned until all the songwriters of a work have been identified, collection societies adding their own unique code for the work to their databases if there is a delay in issuing an ISWC and the (ironic) fact that there is no standardised way to fill out the information for an ISWC.

Other notable attempts to fix things here include:

- The International Standard Name Identifier (ISNI), but, as the report notes, the data in the ISNI registry is not of a high standard and it has not yet been widely adopted in the industry;

- Common Works Registration (CWR) which many publishers have adopted as a way of notifying affiliates and/or sub-publishers of the acquisition of new material – but the format has not been frequently updated and not all sources are using CWR information for their statements;

- Digital Data Exchange (DDEX) which is made up of two standards related to music publishing – the Digital Sales Report for licensees to report the level of sales, usage and/or revenue generated from the distribution of music, alongside information about the music; and the Claim Detail Message standard which is used by rightsholders to make claims in respect of musical works identified in a sales/usage report – and while large music publishers, rights societies and DSPs have implemented them, some smaller independent publishers have not.

There have been moves to utilise new technologies like AI and the blockchain to fix some (or many) of the reporting, matching and standardisation problems here, which reveals a keenness to experiment and find ways out for all those in the system.

As mentioned in the Drowning In Data report, services such as Blokur and Verifi Media are working on solutions to track and manage music rights data using the blockchain and machine learning while payments company Exactuals has used AI for RAI (its bespoke tool for cleaning and enhancing metadata by matching disparate datasets). While blockchain-based solutions can assist greatly here, they do come with a high environmental cost, something that is particularly pertinent in the current debates around NFTs.

Marsden obviously has skin in the game here, but he says that the wider industry still needs to work much more closely with the best in class of new services that are offering tech-based solutions here.

“PROs need to actively engage with this start-up culture, embracing new technologies and experimenting with how to improve efficiency on behalf of the songwriters they represent.”

– Henry Marsden, Creatr

“PROs need to actively engage with this start-up culture, embracing new technologies and experimenting with how to improve efficiency on behalf of the songwriters they represent,” he says. “The danger is that a new breed of tech-focussed collection societies – AMRA and Muserk come to mind – will bring such efficiency to digital collection it will outweigh any potential loss of revenue from excluding other more traditional rights, like broadcast and radio.”

Phil Barry, founder and CEO of Blokur, explains how his company is identifying and addressing issues here for rightsowners and creators.

“One of the key technologies we have developed at Blòkur is a sub-graph matching process,” he says. “We use this any time we need to identify whether two things are the same or unique. For example: merging multi-party compositions; identifying creator pseudonyms; or matching recordings to works.”

He praises what some of the industry-led platforms have achieved so far here.

“In music publishing, one of the biggest developments is undoubtedly the MLC in the US,” he says. “We are seeing a lot of new transparency around both copyright and royalty reporting that I think is going to have a big impact in terms of driving improvements in the medium and longer term. Meanwhile DDEX and CWR continue to play an essential role in enabling different parts of the music industry to speak in the same language.”

“In music publishing, one of the biggest developments is undoubtedly the MLC in the US. We are seeing a lot of new transparency around both copyright and royalty reporting that I think is going to have a big impact.”

– Phil Barry, Blokur

It all comes back, of course, to the data. The old computer science maxim of “garbage in, garbage out” has never been more pertinent than in the case of digital music data. If the data going into the system at the top end is incomplete or simply wrong then the entire system is compromised. Some platforms are there to help clean up such compromised data from fuzzing up the arteries of the system, but there also needs to be renewed emphasis on ensuring that creators and rightsowners are being rigorous with the new data they are now putting in. If not, the mistakes of the past will just keep repeating themselves.

Marsden argues that creators themselves must be more directly involved here and be provided with the tools to ensure that the data they are starting to submit to different platforms and PROs is as watertight as possible.

“In general terms creators have little interest in ISWCs, CWRs and the like,” he says. “Education is vital, but research shows this – or even the direct financial incentive – isn’t enough for creatives to conquer the required administrative battles. Creatr is working to empower songwriters to directly handle their data, giving them the tools to see and correct song registrations in a collaborative effort with peers and industry partners.”

Pieces may be (slowly) starting to fall into place here, but there are a number of ways this can (and should) move next. The emphasis needs to be on creators as allies here – getting them directly involved in improving data – and also finding ways to assist the patchwork of smaller players, such as independent publishers, who do not have the same financial or data resources of the bigger players. If they are not able to keep up with the pack, the whole system suffers. Without everyone pulling together, some problems will persist.

Source: Synchtank’s Drowning in Data report

“Music rights data sets cannot be a closely guarded secret, but must be open to inspection and for transparent audit, facilitating error-checking and improving accuracy by collaboration.”

– Henry Marsden, Creatr

“There’s the well-worn paths of interoperability, data standards and global databases,” says Marsden. “There is clear progress to be made in these areas, but there are deeper underpinning currents. If we all agree that the industry should be built to serve rather than exploit its value creators, there are two interlinked areas for improvement: PRO policies on data sharing; and transparency for creatives to see and control their data registrations globally. Interoperability can only be achieved through willingness to co-operate. Music rights data sets cannot be a closely guarded secret, but must be open to inspection and for transparent audit, facilitating error-checking and improving accuracy by collaboration. The songwriter should participate in this directly – having transparency for ease of correcting errors through a currently opaque global network of databases.”

Barry argues we need to be careful that a bifurcated situation does not arise whereby major players march forward and improve their systems while smaller players are left floundering.

“Although existing standards are well adopted by the biggest music companies, I think there remains an opportunity in making it easier for smaller companies who may not have technical resources to exchange data in standard-compliant ways.”

– Phil Barry, Blokur

“Although existing standards are well adopted by the biggest music companies, I think there remains an opportunity in making it easier for smaller companies who may not have technical resources to exchange data in standard-compliant ways,” he says.

He is, however, optimistic that the steps being taken already by the MLC point to a better future.

“For the bigger picture,” he concludes, “I suspect the transparency brought about with the MLC may bring about a broader agreement that the availability of data benefits everybody by bridging the gaps between silos and shining a light on opportunities for improvement.”

2 comments

Yes,yes,yes – and the solution is ?

Yes,yes,yes – and the solution is ?